Learn More About Florida’s Civil Rights Heroes & Important Landmarks

Learn about the heroes who helped make a stand for equality in the Sunshine State.

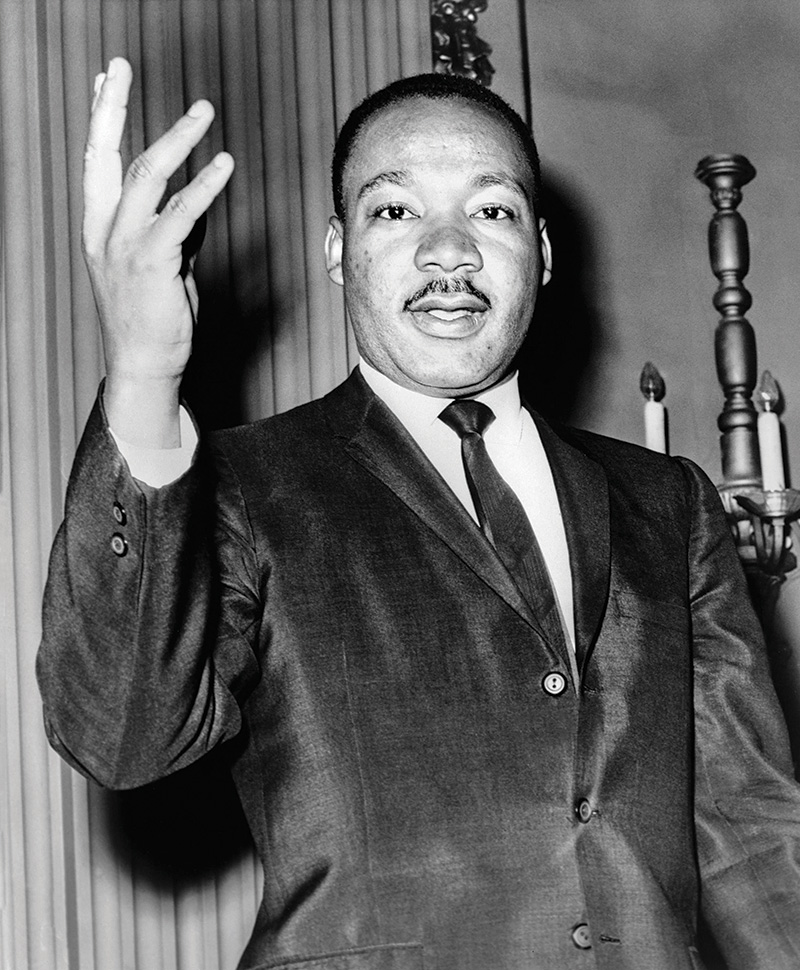

Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., made one visit to Orlando. It was March 6, 1964, just months prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act. ©Dick Demarsico

January 15 marks 96 years since the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; five days later sees the second annual observance of MLK Day as a federal holiday. And though the famed civil rights leader visited Orlando just once before his assassination in 1968, his indelible impact is still felt both here and around the globe.

The Orange County Regional History Center chronicles King’s social justice campaign stop in its ongoing “How Distant Seems Our Starting Place” exhibit. It was March 6, 1964, just months prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act, during a rally at since-demolished Tinker Field. King spoke from the pitcher’s mound to a crowd of 2,000, many seated for the first time in the then “whites-only” grandstand.

But it was far from King’s only visit to Florida—nor was he the state’s only pivotal player in the Civil Rights Movement. Set off along the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, and you’ll discover noteworthy individuals and events throughout Florida that helped make King’s dream of a more perfect union a reality.

“There’s no substitute for standing in the very places where sacrifices were made and history was changed,” says U.S. Civil Rights Trail Marketing Alliance chairman Mark Ezell. “It’s an experience that profoundly resonates.”

Harry T. & Harriette V. Moore Memorial Park & Museum, Mims

Educators and early civil rights pioneers Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore taught in segregated public schools around Brevard County from 1925 to 1946, with Harry serving as principal of the Titusville Negro School. Demanding equal pay for the state’s Black teachers, in 1937 he filed a lawsuit against the Brevard County School Board, in consultation with civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall, the first of its kind in the South.

Three years earlier Harry had founded the area’s first branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and would aid in establishing others, becoming president of the Florida Conference of NAACP branches in 1941. Outspoken against racial violence, he also formed the Florida Progressive Voter’s League, which helped register 100,000 Black voters in the state.

On Christmas night 1951, celebrating their 25th wedding anniversary, the couple retired to their bedroom, where a bomb detonated as they slept. Harry died en route to the hospital; Harriette followed soon after. No one was ever charged.

A replica of the Moore’s home now stands on the site, along with a museum, conference center and reference library, featuring interactive exhibits, Moore family memorabilia, oral histories, educational films and a Civil Rights Movement timeline spanning nearly a century. Tours are offered daily.

Dodgertown became a Florida Heritage Landmark thanks to Jackie Robinson, who spent 10 seasons with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He broke the color barrier on April 15, 1947, as the first African American to be signed to a major league sport. Today, a Vero Beach sports complex bears his name.

Jackie Robinson Training Complex, Vero Beach

served as the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Florida training facility from 1948 until 2008. But its 2014 declaration as a Florida Heritage Landmark has less to do about the site itself than the trailblazing athlete who practiced there: Jackie Robinson.

With Robinson breaking the color barrier on April 15, 1947, as the first African American to be signed to a major league sport, Dodgertown ranks as the first fully integrated Major League Baseball spring training facility in the South. It would be another decade before all MLB clubs followed suit.

Robinson spent 10 seasons with the team, winning the Rookie of the Year Award in his first, and raking up 137 home runs before his retirement in 1956. Elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, his number, 42, was retired league-wide in 1997; he is the only player in MLB history to be so honored.

He scored even more firsts off the field than on. He would go on to become the first Black man named vice president of a Fortune 500 company, the first to co-found a bank and the first African American sports analyst.

Robinson was also a civil rights champion. Serving in the Army during WWII at Fort Hood, Texas, he was court-martialed and honorably discharged for refusing to move to the back of a segregated military bus. He spoke at the 1963 March on Washington, was named one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century by Time magazine and was posthumously awarded both the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1984) and Congressional Gold Medal (2005).

The Vero Beach complex now bearing his name is a multiuse sports facility, where two Florida State League teams play in the Jackie Robinson Celebration Game every April 15 on Jackie Robinson Day.

Sarasota’s Newtown Alive trolley tours are led by community scholars who share personal stories about the Civil Rights Movement. ©Sarasota African American Cultural Coalition

Newtown African American Heritage Trail, Sarasota

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Sarasota’s historically Black neighborhood of Newtown predates the city itself.

Preceded by Angola—aka Sarrazota (at the time, Florida was still under Spanish rule)—the area was largely populated by escaped slaves and Creek and Seminole Indians, from 1812 until 1821, when it became a U.S. territory and was soon after destroyed at the command of President Andrew Jackson.

It later became known as Overtown, a thriving, self-sustaining community of color, before its establishment as Newtown in 1914, with 240 lots on 40 acres developed “exclusively for colored people.” It would remain a haven for thousands until the Jim Crow era of the 1940s and ’50s. The preservation organization Newtown Alive offers a two-hour guided trolley tour that visits 15 historic sites.

“The guided tours on a trolley visit key spots in Sarasota where history happened,” says Vickie Oldham, president of the Sarasota African American Cultural Coalition, Inc. (SAACC) and founder of Newtown Alive. “Onboard are community scholars who share personal stories about the Civil Rights Movement. They witnessed history unfold from a front row seat.”

In addition, says Oldham, a freedom singer leads tour guests in singing the tunes that helped African Americans endure the worst of times during Jim Crow segregation.

“It is an uplifting tour because many of our ancestors survived, thrived and taught their offspring to do the same,” she says.

What really put Newtown on the map was Sarasota’s beautiful beaches and Black residents’ inability to access them. At the time, Florida counted some 825 miles of public beachfront, with only two made accessible to African Americans. Newtown business owner Mary Emma Jones set out to change that.

In 1949 she petitioned city government to live up to its “separate but equal” obligations and create a “colored-only” beach. Though money was eventually allocated, by 1953, no beach had materialized due to adamant opposition by white residents. Following 1954’s U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education ruling that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional, Jones teamed up with local NAACP president Neil Humphrey to organize a series of “wade-in” protests demanding full access to the city’s shoreline.

After church services on Oct. 2, 1955, a caravan of cars steered close to 100 Newtown community members to pristine Lido Beach, where they were met by police and white beachgoers who hurled bottles and derisive insults. So began a weekly desegregation campaign that would last well into the 1960s, long after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

“There are universal themes that characterize Newtown’s history,” says Oldham. “Young leaders led the way and changed the Sarasota community forever. They faced uncertainties (just as we feel today), took risks, handled setbacks, made adjustments, used innate skills and never, ever gave up their search for equality. We should follow their lead.”

Gideon v. Wainwright Historical Marker at the Bay County Courthouse, Panama City

Panama City’s circa-1915 Bay County Courthouse is one of five original Florida courthouses still in use. It’s the marker in front, however, commemorating the landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the Constitution’s Sixth Amendment guaranteed a criminal defendant’s right to counsel if they cannot afford their own, that cements its place in history.

The case centered on Clarence Earl Gideon, who was charged with breaking into the Bay Harbor Pool Hall on June 3, 1961, and stealing $50 from the jukebox, along with $5 in change, a couple of beers and a Coca-Cola. Too poor to hire a defense attorney, Gideon asked that the court provide him one. But the judge denied his request, noting that, consistent with Florida state laws of the time, that statute applied only to capital offense cases.

Gideon was forced to represent himself at trial, where he was found guilty and sentenced to five years in state prison. There, Gideon studied law in the prison library and subsequently wrote a five-page petition in pencil to the Florida Supreme Court asking for his case to be reviewed, claiming his Sixth Amendment rights had been violated. That too was denied.

Undeterred, Gideon appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case, assigning it to powerful Washington D.C. attorney Abe Fortas, who argued on Gideon’s behalf and won. Gideon was granted a retrial, this time with appointed counsel at the government’s expense. The jury deliberated for just one hour before acquitting him of the original charges.

As a result of the Gideon decision, close to 2,000 people were freed from prison in Florida alone.

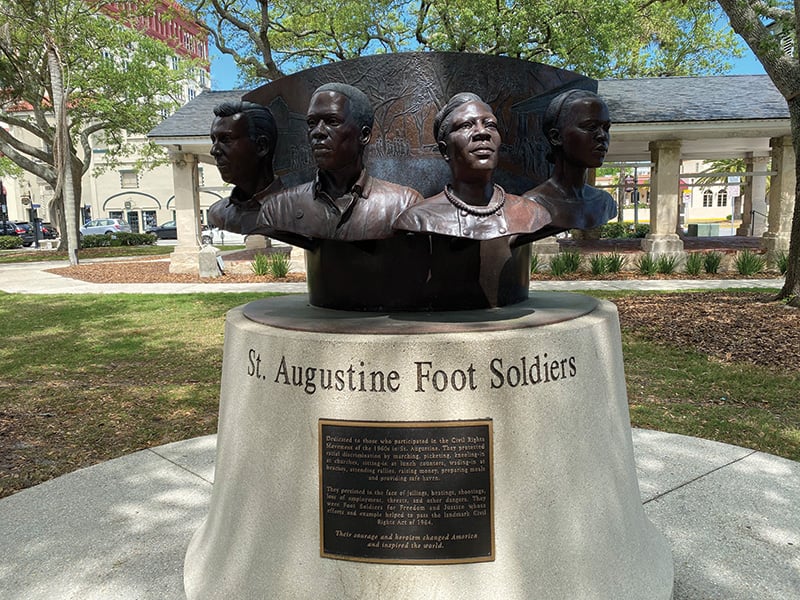

St. Augustine’s Foot Soldiers Monument honors those who protested peacefully to advance the Civil Rights Movement. ©St. Augustine, Ponte Vedra & The Beaches VCB

National Historic Preservation District, St. Augustine

The United States’ oldest city is also home to its first legally sanctioned settlement for free Africans, Fort Mose, founded in 1738. As with Sarasota, escaped slaves seeking freedom from the British colonies of the Carolinas and Georgia were drawn to the area, where the then-ruling Spanish government offered asylum in exchange for their conversion to Catholicism and short-term military service.

Now a National Historic Landmark and state park, the site offers a state-of-the-art museum and annual events, such as its Flight to Freedom living history commemoration (Feb. 20-22).

Fast forward 226 years to 1964, when St. Augustine witnessed a different type of freedom march. With passage of the Civil Rights bill stalled by southern senators conducting a monthslong filibuster, movement leaders Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young and others gathered in the city to conduct peaceful protests demanding racial equality.

There were sit-ins at restaurants and Woolworth lunch counters and nightly marches around the Plaza de la Constitucion that were countered with verbal and physical assaults. The demonstrations resulted in so many arrests (including Dr. King’s own), the jail was overrun, and detainees were confined to an outdoor stockade during the day. The ACCORD Freedom Trail leads visitors to 31 markers of significant sites.

The continued confrontations brought national news coverage and attention. The conflicts culminated June 18, 1964, with protesters—both black and white—jumping into the Monson Motel pool, where photographers captured shots of the owner pouring muriatic acid into the water.

The Senate passed the Civil Rights Act the following day.